People Keep Waking Up as Different People and Finding Each Other Again

The forgotten medieval habit of 'two sleeps'

For millennia, people slept in two shifts – once in the evening, and one time in the morning. But why? And how did the habit disappear?

I

It was around 23:00 on 13 April 1699, in a pocket-sized village in the north of England. Nine-yr-old Jane Rowth blinked her optics open and squinted out into the moody evening shadows. She and her mother had just awoken from a short slumber.

Mrs Rowth got up and went over to the fireside of their pocket-size dwelling house, where she began smoking a pipe. Just so, two men appeared by the window. They called out and instructed her to get ready to get with them.

Equally Jane later on explained to a courtroom, her mother had evidently been expecting the visitors. She went with them freely – but outset whispered to her daughter to "lye still, and shee would come againe in the morning". Perhaps Mrs Rowth had some nocturnal task to consummate. Or maybe she was in problem, and knew that leaving the house was a take a chance.

Either way, Jane'due south mother didn't get to continue her promise – she never returned home. That nighttime, Mrs Rowth was brutally murdered, and her body was discovered in the following days. The criminal offence was never solved.

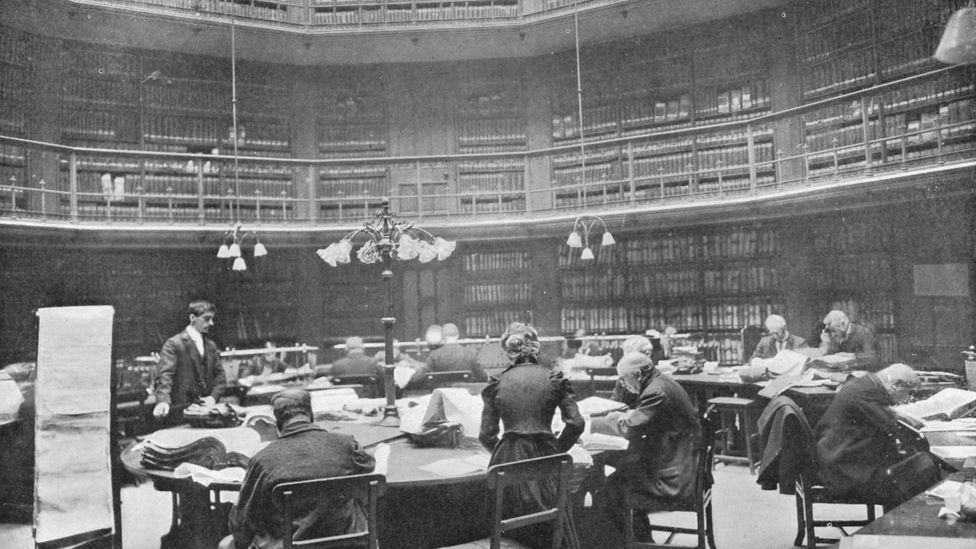

About 300 years later, in the early 1990s, the historian Roger Ekirch walked through the arched entranceway to the Public Record Office in London – an imposing gothic building that housed the UK's National Athenaeum from 1838 until 2003. At that place, among the countless rows of ancient vellum papers and manuscripts, he found Jane's testimony. And something about it struck him as odd.

Originally, Ekirch had been researching a volume near the history of night-fourth dimension, and at the time he had been looking through records that spanned the era between the early Center Ages and the Industrial Revolution. He was dreading writing the affiliate on slumber, thinking that it was not merely a universal necessity – simply a biological constant. He was sceptical that he'd observe annihilation new.

So far, he had found court depositions particularly illuminating. "They're a wonderful source for social historians," says Ekirch, a professor at Virginia Tech, US. "They comment upon activity that's often unrelated to the criminal offence itself."

But every bit he read through Jane's criminal deposition, two words seemed to conduct an repeat of a particularly tantalising particular of life in the 17th Century, which he had never encountered earlier – "starting time slumber".

"I tin cite the original document almost verbatim," says Ekirch, whose exhilaration at his discovery is palpable even decades later.

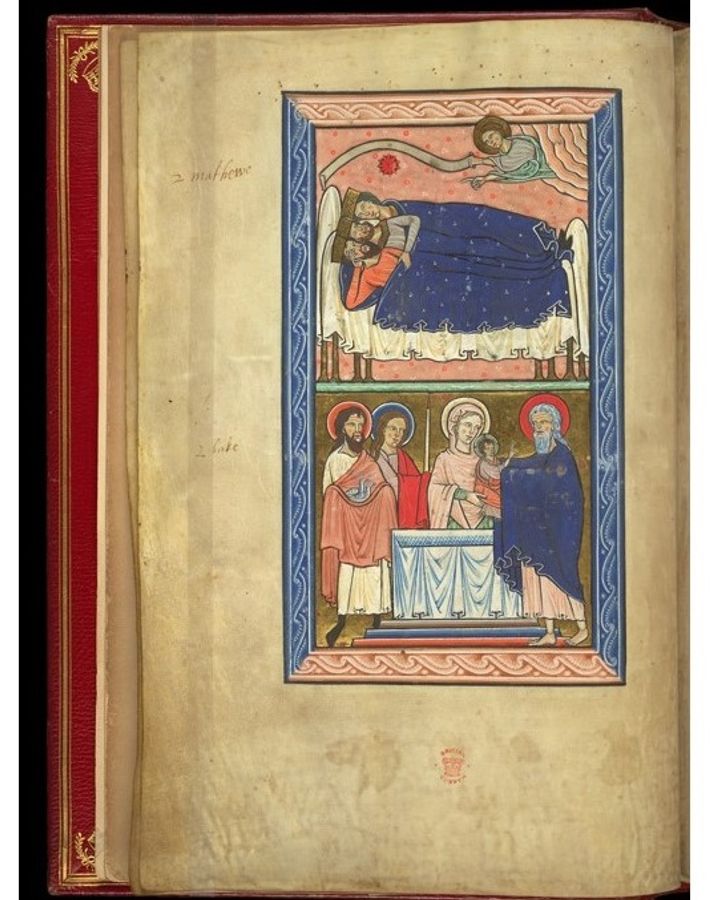

In the Middle Ages, communal sleeping was entirely normal – travellers who had just met would share the aforementioned bed, as would masters and their servants (Credit: British Library)

In her testimony, Jane describes how only before the men arrived at their abode, she and her female parent had arisen from their first sleep of the evening. At that place was no farther explanation – the interrupted sleep was merely stated matter-of-factly, equally if information technology were entirely unremarkable. "She referred to it every bit though it was utterly normal," says Ekirch.

A first slumber implies a second sleep – a night divided into two halves. Was this just a familial quirk, or something more than?

An attendance

Over the coming months, Ekirch scoured the archives and found many more references to this mysterious phenomenon of double sleeping, or "biphasic sleep" every bit he later chosen it.

Some were fairly banal, such every bit the mention by the weaver Jon Cokburne, who simply dropped it into his testimony incidentally. Just others were darker, such as that of Luke Atkinson of the Eastward Riding of Yorkshire. He managed to squeeze in an early forenoon murder between his sleeps one dark – and co-ordinate to his wife, often used the time to frequent other people's houses for sinister deeds.

When Ekirch expanded his search to include online databases of other written records, it shortly became articulate the phenomenon was more widespread and normalised than he had always imagined.

For a start, commencement sleeps are mentioned in one of the most famous works of medieval literature, Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (written between 1387 and 1400), which is presented equally a storytelling competition betwixt a grouping of pilgrims. They're too included in the poet William Baldwin'south Beware the Cat (1561) – a satirical book considered by some to be the first e'er novel, which centres around a homo who learns to empathise the language of a group of terrifying supernatural cats, one of whom, Mouse-slayer, is on trial for promiscuity.

Merely that's just the outset. Ekirch constitute casual references to the system of twice-sleeping in every conceivable form, with hundreds in letters, diaries, medical textbooks, philosophical writings, newspaper articles and plays.

The practice even made information technology into ballads, such every bit "Quondam Robin of Portingale. "…And at the wakening of your outset sleepe, You shall have a hot drink fabricated, And at the wakening of your side by side sleepe, Your sorrows will have a slake…"

Biphasic sleep was non unique to England, either – information technology was widely practised throughout the preindustrial world. In France, the initial sleep was the "premier somme"; in Italy, it was "primo sonno". In fact, Eckirch plant evidence of the habit in locations every bit afar as Africa, Due south and Southeast Asia, Australia, South America and the Heart East.

Like many Romans, the historian Livy may have been a practitioner of biphasic slumber – he alludes to the method in his magnum opus, The History of Rome (Credit: Alamy)

One colonial account from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1555 described how the Tupinambá people would consume dinner after their kickoff sleep, while some other – from 19th Century Muscat, Oman – explained that the local people would retire for their first sleep earlier 22:00.

And far from being a peculiarity of the Heart Ages, Ekirch began to suspect that the method had been the dominant way of sleeping for millennia – an ancient default that we inherited from our prehistoric ancestors. The start tape Ekirch plant was from the 8th Century BC, in the 12,109-line Greek epic The Odyssey, while the concluding hints of its existence dated to the early 20th Century, earlier it somehow slipped into oblivion.

How did it piece of work? Why did people do it? And how could something that was once then completely normal, have been forgotten and so completely?

A spare moment

In the 17th Century, a nighttime of slumber went something similar this.

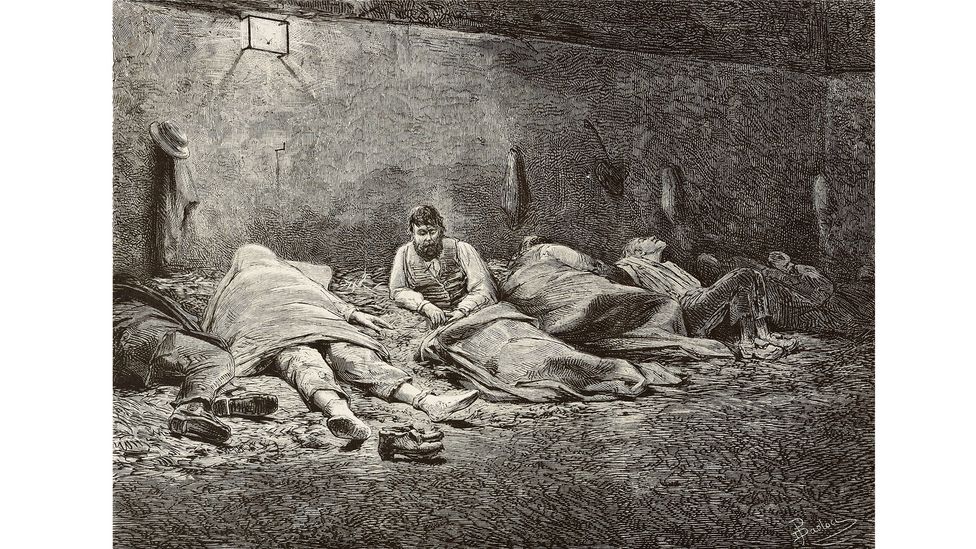

From as early every bit 21:00 to 23:00, those fortunate enough to afford them would begin flopping onto mattresses stuffed with straw or rags – alternatively information technology might accept contained feathers, if they were wealthy – ready to sleep for a couple of hours. (At the bottom of the social ladder, people would accept to make do with nestling downwards on a scattering of heather or, worse, a blank globe flooring – possibly even without a blanket.)

At the time, most people slept communally, and often found themselves snuggled up with a cosy assortment of bedbugs, fleas, lice, family members, friends, servants and – if they were travelling – full strangers.

To minimise whatsoever clumsiness, slumber involved a number of strict social conventions, such as avoiding physical contact or too much fidgeting, and there were designated sleeping positions. For example, female children would typically lie at ane side of the bed, with the oldest nearest the wall, followed by the mother and father, and then male person children – again arranged past historic period – then non-family members.

A couple of hours later, people would begin rousing from this initial slumber. The night-time wakefulness commonly lasted from effectually 23:00 to about 01:00, depending on what time they went to bed. It was not generally caused past dissonance or other disturbances in the night – and neither was it initiated by any kind of warning (these were just invented in 1787, by an American human being who – somewhat ironically – needed to wake upward on time to sell clocks). Instead, the waking happened entirely naturally, merely equally it does in the morning.

The period of wakefulness that followed was known as "the watch" – and it was a surprisingly useful window in which to get things done. "[The records] describe how people did just nearly anything and everything after they awakened from their first sleep," says Ekirch.

Communal sleeping meant that people usually had someone to chat with when they woke up for "the watch" (Credit: Getty Images)

Nether the weak glow of the Moon, stars, and oil lamps or "rush lights" – a kind of candle for ordinary households, made from the waxed stems of rushes – people would tend to ordinary tasks, such every bit adding wood to the fire, taking remedies, or going to urinate (oft into the fire itself).

For peasants, waking up meant getting back down to more than serious piece of work – whether this involved venturing out to bank check on farm animals or carrying out household chores, such as patching material, combing wool or peeling the rushes to be burned. I servant Ekirch came beyond fifty-fifty brewed a batch of beer for her Westmorland employer i dark, between midnight and 02:00. Naturally, criminals took the opportunity to skulk around and make trouble – like the murderer in Yorkshire.

Simply the watch was also a time for religion.

For Christians, there were elaborate prayers to be completed, with specific ones prescribed for this verbal parcel of time. 1 begetter called it the most "assisting" hour, when – after digesting your dinner and casting off the labours of the world – "no one will look for you except for God".

Those of a philosophical disposition, meanwhile, might employ the watch as a peaceful moment to ruminate on life and ponder new ideas. In the belatedly 18th Century, a London tradesman even invented a special device for remembering all your almost searing nightly insights – a "nocturnal remembrancer", which consisted of an enclosed pad of parchment with a horizontal opening that could be used as a writing guide.

Simply most of all, the watch was useful for socialising – and for sex.

As Ekirch explains in his volume, At Day'due south Close: A History of Nighttime, people would often but stay in bed and chat. And during those strange twilight hours, bedfellows could share a level of informality and coincidental conversation that was hard to attain during the day.

For husbands and wives who managed to navigate the logistics of sharing a bed with others, it was too a convenient interval for concrete intimacy – if they'd had a long day of transmission labour, the outset sleep took the edge off their exhaustion and the period later was thought to be an excellent time to conceive copious numbers of children.

One time people had been awake for a couple of hours, they'd commonly head dorsum to bed. This next step was considered a "forenoon" slumber and might last until dawn, or after. Only as today, when people finally woke upward for adept depended on what time they went to bed.

The Public Record Office was home to thousands of criminal depositions from the medieval era, which are now kept at The National Archives in Kew (Credit: Getty Images)

An aboriginal adaptation

Co-ordinate to Ekirch, at that place are references to the system of sleeping twice brindled throughout the classical era, suggesting that it was already common so. Information technology's casually dropped into works by such illustrious figures as the Greek biographer Plutarch (from the First Century AD), the Greek traveller Pausanias (from the Second Century AD), the Roman historian Livy and the Roman poet Virgil.

Later, the exercise was embraced by Christians, who immediately saw the watch'southward potential every bit an opportunity for the recital of psalms and confessions. In the 6th Century Advertizement, Saint Benedict required that monks ascent at midnight for these activities, and the idea eventually spread throughout Europe – gradually filtering through to the masses.

Just humans aren't the simply animals to find the benefits of dividing up slumber – it'southward widespread in the natural earth, with many species resting in two or even several separate stretches. This helps them to remain active at the nearly benign times of twenty-four hours, such equally when they're most likely to discover food while avoiding ending up as a snack themselves.

I case is the ring-tailed lemur. These iconic Madagascan primates, with their spooky red eyes and upright black-and-white tails, accept remarkably similar sleeping patterns to preindustrial humans – they're "cathemeral", meaning they're up at dark and during the twenty-four hour period.

"There are broad swaths of variability among primates, in terms of how they distribute their activeness throughout the 24-hour flow," says David Samson, director of the sleep and human being evolution laboratory at the University of Toronto Mississauga, Canada. And if double-sleeping is natural for some lemurs, he wondered: might information technology exist the fashion we evolved to sleep too?

Ekirch had long been harbouring the aforementioned hunch. But for decades, at that place was nothing concrete to prove this – or to illuminate why it might have vanished.

Then back 1995, Ekirch was doing some online reading belatedly one night when he found an commodity in the New York Times virtually a sleep experiment from a few years earlier.

The inquiry was conducted by Thomas Wehr, a sleep scientist from the National Institute of Mental Health, and involved 15 men. Afterward an initial week of observing their normal sleeping patterns, they were deprived of artificial illumination at dark to shorten their hours of "daylight" – whether naturally or electrically generated – from the usual sixteen hours to merely ten. The residual of the time, they were bars to a bedroom with no lights or windows, and fully enveloped in its velvety blackness. They weren't allowed to play music or do – and were nudged towards resting and sleeping instead.

Ekirch wonders if today people might remember fewer dreams than our ancestors did, because it'southward less mutual to wake up in the eye of the night (Credit: Alamy)

At the first of the experiment, the men all had normal nocturnal habits – they slept in 1 continuous shift that lasted from the tardily evening until the forenoon. Then something incredible happened.

Afterward 4 weeks of the 10-hour days, their sleeping patterns had been transformed – they no longer slept in ane stretch, but in 2 halves roughly the aforementioned length. These were punctuated by a one-to-three-hour period in which they were awake. Measurements of the sleep hormone melatonin showed that their cyclic rhythms had adjusted as well, then their sleep was altered at a biological level.

Wehr had reinvented biphasic sleep. "It [reading about the experiment] was, apart from my wedding and the birth of my children, probably the most exciting moment in my life," says Ekirch. When he emailed Wehr to explain the extraordinary friction match betwixt his ain historical research, and the scientific written report, "I think I tin tell y'all that he was every fleck as exhilarated as I was," he says.

For much of human history, those who couldn't afford a bed had to sleep on straw or other stale vegetation (Credit: Getty Images)

More recently, Samson's own research has backed up these findings – with an exciting twist.

Back in 2015, together with collaborators from a number of other universities, Samson recruited local volunteers from the remote community of Manadena in northeastern Madagascar for a written report. The location is a large hamlet that backs on to a national park – and there is no infrastructure for electricity, so nights are well-nigh as dark every bit they would have been for millennia.

The participants, who were mostly farmers, were asked to article of clothing an "actimeter" – a sophisticated activeness-sensing device that can exist used to runway sleep cycles – for 10 days, to track their slumber patterns.

"What we establish was that [in those without artificial light], there was a period of action right after midnight until about 01:00-01:xxx in the morning," says Samson, "so it would drop back to sleep and to inactivity until they woke up at 06:00, unremarkably congruent with the rising of the Sun."

Every bit information technology turns out, biphasic sleep never vanished entirely – information technology lives on in pockets of the globe today.

A new social pressure

Collectively, this enquiry has also given Ekirch the caption he had been craving for why much of humanity abandoned the two-slumber system, starting from the early 19th Century. Every bit with other recent shifts in our behaviour, such as a motion towards depending on clock-time, the answer was the Industrial Revolution.

In the 17th Century, wealthy elites usually slept in iv-poster wooden beds with curtains, to go along the occupant warmer and exclude the prying eyes of visitors (Credit: Alamy)

"Artificial illumination became more than prevalent, and more than powerful – showtime at that place was gas [lighting], which was introduced for the get-go time ever in London," says Ekirch, "and and then, of grade, electric lighting toward the stop of the century. And in addition to altering people'south circadian rhythms. artificial illumination also naturally allowed people to stay upwards later on."

Notwithstanding, though people weren't going to bed at 21:00 anymore, they nevertheless had to wake up at the same time in the morning – and then their rest was truncated. Ekirch believes that this made their sleep deeper, because it was compressed.

Likewise as altering the population'due south circadian rhythms, the artificial lighting lengthened the get-go sleep, and shortened the 2d. "And I was able to trace [this], almost decade by decade, over the course of the 19th Century," says Ekirch.

(Intriguingly, Samson'due south report in Madagascar involved a second part – in which one-half the participants were given artificial lights for a week, to see if they made any deviation. And this case, the researchers constitute that it had no affect on their segmented sleep patterns. Withal, the researchers betoken out that a week may not be long enough for artificial lights to atomic number 82 to major changes. Then the mystery continues…)

Even if artificial lighting was not fully to blame, by the stop of the 20th Century, the division between the two sleeps had completely disappeared – the Industrial Revolution hadn't just changed our technology, but our biology, likewise.

A new anxiety

I major side-effect of much of humanity'south shift in sleeping habits has been a modify in attitudes. For i thing, nosotros quickly began shaming those who oversleep, and developed a preoccupation with the link between waking upward early and existence productive.

"Simply for me, the virtually gratifying attribute of all this," says Ekert, "relates to those who suffer from center-of-the-nighttime insomnia." He explains that our sleeping patterns are now and so altered, any wakefulness in the middle of the night can lead us to panic. "I don't mean to make light of that – indeed, I suffer from sleep disorders myself, really. And I have medication for information technology… " Simply when people learn that this may have been entirely normal for millennia, he finds that it lessens their anxiety somewhat.

Nevertheless, before Ekirch's research spawns a spin off of the Paleo diet, and people showtime throwing away their lamps – or worse, artificially splitting their sleep in two with alarm clocks – he'south keen to stress that the abandonment of the two-sleep system does non mean the quality of our slumber today is worse.

Despite near-constant headlines about the prevalence of sleep problems, Ekirch has previously argued that, in some ways, the 21st Century is a golden historic period for sleep – a time when virtually of united states no longer have to worry well-nigh being murdered in our beds, freezing to death, or flicking off lice, when we can sleep without hurting, the threat of fire, or having strangers snuggled upwards adjacent to us.

In short, single periods of sleep might not exist "natural". And yet, neither are fancy ergonomic mattresses or modern hygiene. "More seriously, there'due south no going back because weather accept changed," says Ekirch.

So, we may be missing out on confidential midnight chats in bed, psychedelic dreams, and night-fourth dimension philosophical revelations – but at to the lowest degree we won't wake up covered in aroused red bites.

--

* The image of The Dream of the Magi is used with the kind permission of the British Library, where information technology forms part of their Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

--

Zaria Gorvett is a senior journalist for BBC Time to come and tweets@ZariaGorvett

--

Join one million Future fans by liking the states on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If yous liked this story, sign upward for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List" – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Futurity, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220107-the-lost-medieval-habit-of-biphasic-sleep

0 Response to "People Keep Waking Up as Different People and Finding Each Other Again"

Post a Comment